The lessons of terror

by Kathleen LaCamera

St. Petersburg Times - published 1 November 2001

Some of the people of Northern Ireland hope that their experiences living amid the constant threat of violence will help those in the United States new to terrorism.

BELFAST, Northern Ireland -- Against a backdrop of British soldiers and armored vehicles, a young Catholic mother stoops to give her toddler a baby bottle. Another crosses herself as an air horn goes off. Only the day before, Protestant paramilitaries announced they would shoot Catholic parents who tried to walk their children to the main entrance of the local Catholic elementary school. These women have been praying that today their families will be able to get to and from school without incident.

BELFAST, Northern Ireland -- Against a backdrop of British soldiers and armored vehicles, a young Catholic mother stoops to give her toddler a baby bottle. Another crosses herself as an air horn goes off. Only the day before, Protestant paramilitaries announced they would shoot Catholic parents who tried to walk their children to the main entrance of the local Catholic elementary school. These women have been praying that today their families will be able to get to and from school without incident.

For those making the school run at Holy Cross Girls Primary School in Belfast, terrorism is a fact of daily life.

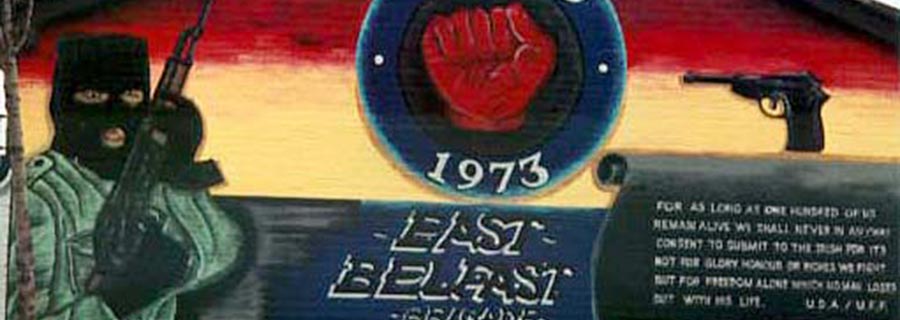

Since the 1970s, the people of Northern Ireland have lived with terrorism on their doorstep. Sectarian violence between Catholics and Protestants has claimed the lives of almost 4,000 people and affected countless others. In recent weeks, hopes for the peace process have risen substantially with the announcement that Catholic paramilitaries, under the banner of the Provisional IRA, have begun to disarm or decommission their weapons. But despite this significant move, other Catholic and Protestant paramilitary groups still hang on to their guns and bombs and their commitment to violence.

So even as the peace process goes on, ordinary people know that terrorism continues to be part and parcel of life in Northern Ireland. Some who have lived through these hardships hope their hard-won experience will help others, particularly in the United States, in their struggle against terrorism.

Standing up to the bully

Brendan Bradley goes up to Holy Cross School every day to walk his nieces and their daughters down the street, past scores of local Protestant residents. Armed security forces line the route to keep residents and parents apart. The protesters want Catholic parents to use a different school entrance, one that does not take them through the Protestant neighborhood bordering the school. This sectarian stand-off is only the latest chapter in 30 years of the Troubles in Northern Ireland. During that period, five members of Bradley's family have been killed.

"You have to stand up to the bully," Bradley said. "It's wrong to stop a child from going to school."

But Bradley, who helped set up the Survivor and Trauma Center, would be the first to say that he has no time for those who advocate revenge in response to terrorism. In 1976 his youngest brother, Francis, was murdered by Protestant paramilitaries. Not long after, Bradley was approached by Catholic paramilitaries who told him two people would die in revenge for his brother's death. When he said he did not want that, Bradley was told it wasn't his decision.

"Revenge won't help. How can you know how much you'll need? Ten bodies? Two hundred, 2,000? A whole country? What will sort you out? A little bit of righteousness and a whole lot of wrongness is a righteousness that is too costly," he said.

Beryl Kelly also has little use for revenge. This Protestant mother of five says she allowed none of the bitterness and suspicion toward Catholics she saw in some of her Protestant neighbors to take root in her life.

Fifteen years ago, Kelly was caught up in an ambush of British troops by IRA paramilitaries as she was walking to her car. In military terms, Kelly was "collateral damage" -- a civilian unlucky enough to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. The sheer force of a nearby rocket blast knocked her out, severely damaging her inner ear. Even after the incident, she refused to make Catholics her enemy.

When rioting broke out on her doorstep and the pipe bombs were going off, it was Kelly's Catholic neighbors who took her children into their homes in the middle of the night.

"We were all like a large family. We never asked whether anyone was Catholic or Protestant. We just helped each other," she said. "That was the key to it."

Kelly's experience is refreshing in a place where everything -- the names you choose for your children, the place you live, even the sports you play -- places you on one side or the other of a religious divide. From birth, whether you are Christian, atheist or something else, you are marked as belonging to the Catholic or the Protestant side, a member of one tribe or the other.

It is out of that deeply divided experience that human rights commissioner and Irish Methodist president Harold Good says that Americans, in the wake of the Sept. 11 attacks, must guard against reprisals on Muslims. He suggests that now, more than ever, people need to cross religious and cultural boundaries.

"It is very important to reach out visibly to those in our community who might be associated with "the enemy,' " he said.

There are lessons to be learned from Northern Ireland's history, he says.

"If we had only listened 30 years ago. We've learned we can unleash all of our strength and force and not deal with the problems here. We've learned there is no military solution to our problem," he said.

Doug Baker of Northern Ireland's Mediation Network points out that violence is "interactive."

"Nothing justifies the events of Sept. 11, but it's essential that we seek to understand everything that may have contributed to it. This involves asking hard questions not only about "them,' but about ourselves."

Baker and the Mediation Network are involved in conflict resolution ranging from simple disputes between co-workers to brokering solutions for whole communities, such as the parents and residents involved with Holy Cross School. So far, their attempts at Holy Cross have failed, and Mediation Network counselors have withdrawn to allow a cooling-off period.

Baker believes strongly that it is in the best interests of the United States and the rest of the world to understand what could drive a young man to fly a plane into a skyscraper. Simply labeling such an act as "evil" may curtail the search for more complex answers that could help prevent terrorism in the future.

"If you really want to rid the world of terrorism, put as much energy into removing the motivation for it as you do into mechanisms for preventing it," he said.

Seeing the other side

Bertie Laverty confesses she would have joined the IRA as a teenager if she had been a boy. Laverty grew up in what she describes as a very Nationalist (Catholic) neighborhood and never met a Protestant until she went to college. She remembers when she was a girl young men, including her father, being regularly roughed up by Protestant police officers. When the IRA killed police officers in bomb attacks, she says, she and her friends used to celebrate.

"We didn't know them," she said. "We didn't even see them as people."

Laverty's transformation happened after going to college, when she started working with both Catholics and Protestants on cross-community projects aimed at helping families and young people. Until then she thought it would make her "less of a Catholic" to work cooperatively with Protestants.

"I thought it would mean that you belonged nowhere. Now I realize that it's only when you have a sense of security about who you are and where you come from that you can be open to others."

Laverty understands what motivates Catholics who turn to terrorism, even though she no longer condones it. She now directs a community center called Fourth Spring, which offers a range of cross-community activities to Catholics and Protestants living along the Springfield Road in West Belfast. The center is based in a Protestant church. Many who visit the center have rarely, if ever, spoken to someone of the "opposite" faith before walking through its doors.

Laverty says her work focuses on change at the grass roots level. She believes peace in Northern Ireland will ultimately be built one relationship at a time. She tells the story of a young woman who said her mother would have "rolled over in her grave" to know her daughter had crossed the Springfield Road to mix with Protestants at a moms and toddlers group. The woman told Laverty that she had quite liked the Protestants she had met at the center, but could not imagine they were typical.

Fighting the deeply ingrained attitudes that have allowed, and even encouraged, terrorism to flourish in Northern Ireland is an ongoing struggle. David Ervine knows how entrenched such hatred can be. He spent 11 years in prison for his involvement with Protestant paramilitary activities. Now he is an elected representative to the Northern Ireland Assembly and played a role in bringing about a Loyalist paramilitary cease-fire crucial to the peace process.

Ervine also knows how hard it is to choose peace when war is what everyone expects. "Peace is harder to create and defend than is war. For leaders, peace is more dangerous than administering war. This is not just a Northern Ireland thing, but a human thing as well. The more we understand that, the more we have a chance to find solutions," he said.